News

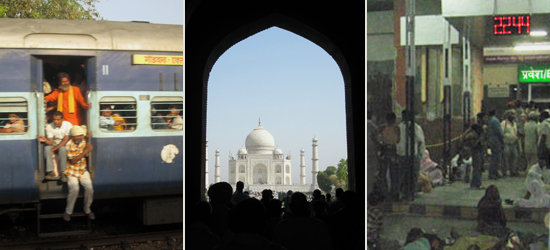

Fluorescents reflecting on the inside of the train windows make it impossible to see out as we pull into the New Delhi station around 10 pm, back from a day-trip to the Taj Mahal. So we have no clue. We file slowly out of the air-conditioned first-class car into the sticky, 100-degree heat and onto a dusty concrete platform that is nothing less than carpeted in humanity: sleeping, sitting, eating, talking, standing, lounging, smoking, cradling, shuffling, cuddling, walking and, frequently, maneuvering a large bundle of belongings, in sandals and saris and ballooning shorts, open shirts and khakis, over every square centimeter. We edge, mostly sideways, through this density toward the pedestrian overpass that will deposit us on the opposite platform that leads outside the station. We hold hands, like we never do anymore, tightly, but functionally. We’ve read about stampedes in those undifferentiated foreign places that seem exotic to gringos. We don’t talk about it. But we’re all pretty sure that one spark and people would die. And maybe some of those people would be us.

The stairs are impassable. But somehow as you lift your foot to the first step you find a toehold that you didn’t see a moment before or that wasn’t there. Like some gelatin river, the crowd haltingly, imperceptibly flows around you, even when the crowd is not moving, and you flow around the crowd. You make it to the overpass and glance back down the stairs to see who you’ve lost, maybe forever. Where’s your friend from Australia? Where’s the Indian account executive who’s been assigned as your guide? No time to do anything about it. You have to hold that hand and keep flowing.

Up on the overpass, there are many people asleep, many, many people, whole families lying on their sides, spooning in the pathway (or where the pathway could be). Some of them have laid down a swatch of cloth, most are on the grimy concrete. Tiny old, white-haired grandmothers and dark brown grandfathers, too old to be here; three-, four- and five-year-olds, too young — along with parents and uncles and aunts and neighbors, too. Intermingled are huddled women from a village or slum, circled, facing each other, hiding in plain sight, as well as seated, silent men, looking serious together, like they share some profound determination. You step like a toe-dancer, so as not to break tiny old-lady legs or tip over and crush a toddler with your well-fed gringo heft. You can’t escape the feeling that you’ve stepped into a movie. Gandhi, of course, the only cliche you know about India. You are a rich, ignorant gringo, no doubt about it. But, just look.

Descending the stairway on the other side, you worry about stumbling on a leg or a bundle and pitching down onto the platform 25-feet below, killing others and maiming yourself and maybe pulling her down with you. You loosen your grip on the hand. You’re almost there. But now that your subconscious thinks the danger is nearly passed, it allows you the luxury of outright fear, and your heart beats harder.

On this side of the station, the people aren’t only all over the platform, they’re all over the tracks, many, many people, mostly men, seated on the cross-ties between the rails, almost all facing west (where the next train will come from?). It looks like a nonviolent protest. From Gandhi. But it’s really just people on the tracks because there’s no room on the platform.

You make it down the stairs and cross the platform and glance back again. And there, way in the back of the procession, is the Australian. And there’s the AE. You pass through the relatively modest, Victorian-era waiting room (modest, relative to the Delhi area’s nine million population) and out into the driveway in front, which is jammed with standard black taxis, tricycle taxis, jitneys, buses and bikes. As your eyes adjust to the dimmer light, everywhere you look, every square centimeter that’s not covered by taxis and buses is, once again, covered by people — asleep, huddling, visiting, cooking, waiting. People, it feels like, as far as the eye can see.

Our intrepid band finally manages to reconstitute outside. The Indian chaperone says he’s never seen anything like it either. It’s not like this, he says. It’s not like this, you think, it’s not like the cliche. But it’s really not — the first thing you noticed arriving in India was that it had a vibrant, growing, robust and populous middle class. In the fancy hotel, you and her were the only gringos, alongside a lot of prosperous Indian families and businessmen. In the streets — along with the janky tricycles and occasional goat or cow — BMWs and Audis, too, with Indians at the wheel. The cliche is that India’s a hopelessly impoverished mess — and the hordes of beggars and sidewalk sleepers certainly support that point of view. But the truth, or as much as a gringo can glean of it, is clearly more than that. And, as a writer, you want to return home and not just re-tell the cliche. Outside the train station, your heart slows, and you release the hand. The Indian guide inquires of someone in the crowd and discovers there is a religious holiday coming up and these people are pilgrims traveling to the holy site. Because it’s not like this, ever, he assures us.

As you wait for the hired bus, something on the roof of the station catches your eye. You look up and see a band of monkeys lope across the eaves and hide behind the sign that says New Delhi.