History of The Tip

The ruins of La Punta would sit as mute testimony to the incendiary ignorance of citizen vigilantes for nearly a decade. Around it grew a dense district of publick houses catering to “saylors from the sea” and “scarlet laydies” and soliciting “the trade and custom of rounders and riff-raff.” But nothing was ever built on the site of the fire. Some said it was haunted, that at night a large, loud, Russian-speaking apparition would regularly rise from the ashes and seize the lapels of local tipplers — who would literally tip over in terror. Some said that, with its uninterrupted history of larceny, murder and mayhem, the place was just bad luck.

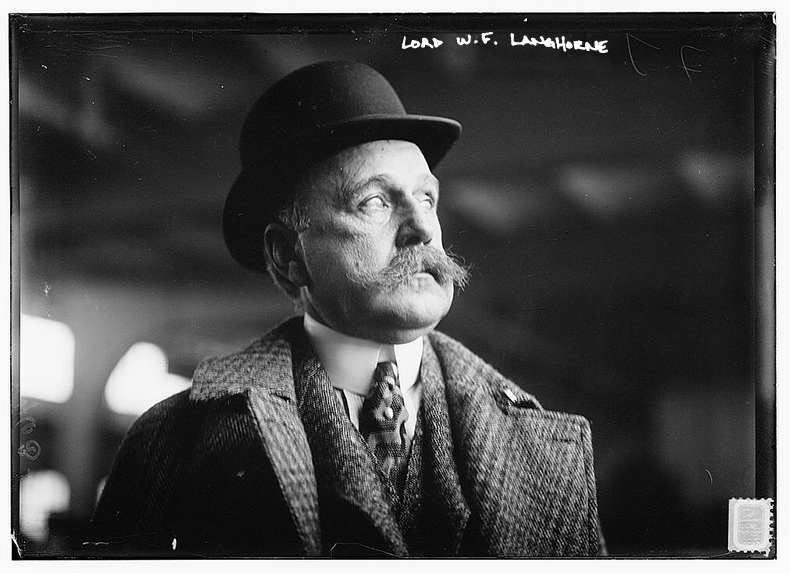

Enter Lord Langhorne.

It’s unclear if he ever really was a British Lord. Nevertheless he carried himself like a king — a benevolent and beloved eminence of early San Francisco, who always referred to himself in the third person and dispensed good cheer (and, on occasion, bad “cheques”) to all he met. “Lord Lucky,” they called him, because he always seemed to narrowly escape disaster, was the perfect proprietor for the resurrection of the Typ, which in his typically grandiose — and inescapably British — fashion, he re-named The Typpler’s Golden Goblet & Goat.

Where the other waterfront pubs topped out at two stories, the Goat, as people took to calling it, reached five, organized as follows: a tavern with a piano and small stage on the first floor; a restaurant on the second; a rooming house on floors three and four; and, finally, on the tip-top, Lord Lucky’s private lair, the place where he would seduce investors no less than the ladies he had hired to perform downstairs in the tavern (and sometimes upstairs in the rooming house).

The Goat and its owner thrived in San Francisco and were widely seen as introducing a new level of bonhomie to this then gritty city by the bay (in other words, this was the place politicians, generals and railroad barons liked to visit when they wanted to, if you will, let their hair down). Langhorne built a mansion, the very first, atop Nob Hill (later, his heir would sell it to the Central Pacific Railroad’s Leland Stanford). And whenever trouble erupted at the Goat — a knifing or bludgeoning (and there were many) — Lord Lucky’s close relationships with such august figures of authority as Sam Brannan (he of the street and the deeply suspect million-dollar stash) ensured that repercussions rarely ensued.

For 23 years, the Goat was the toast of the town. And then, one day, the munificent Langhorne abruptly disappeared, at the tender age of 52. No note, no body, “no earthly explanation,” according to the San Francisco Call of 13 October 1843.

··········

Previous · Chapter 2

La Punta and the Curyous ailment

··········

Next · Chapter 4

Of practices Manly