News

She wouldn’t want me telling you this — the first thing to know about Roni Hoffman is that, unlike some of us, she tends toward the taciturn. In fact, after more decades together than we’d ever admit, I’m still hearing new details of her story.

But it’s a helluva story.

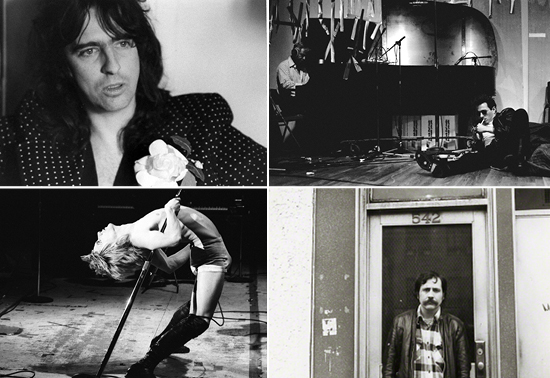

Her boyfriend was among the first of the dubious breed that came to be known as rock critics. You see, back in the day, there were these things called daily newspapers and each one had a middle-aged guy who wrote about jazz and that’s who the dailies would send to cover rock concerts, often with laughable results, at least to rock fans. But along came a publication called Crawdaddy, the first real rock magazine, a year before Rolling Stone. Sandy Pearlman wrote for it. And so did Roni’s b.f. Which meant that at 17 she got to hang out with Jimi Hendrix backstage at a club in Greenwich Village, and later to attend the press conference atop the Pan Am building where, in a publicity stunt, the nascent guitar god had just landed in a helicopter. She was at the Dom on St. Mark’s Place when the Velvet Underground played, and a 17-year-old Jackson Browne opened. She was at Patti Smith’s first poetry reading, before Lenny Kaye strummed along on guitar, and then backstage at the Bitter End when Bob Dylan stopped by to pass Patti the torch as rock ‘n’ roll poet laureate.

Jim Morrison put his arm around Roni’s shoulders and a joint in her mouth. Mick Jagger just put his arm around her shoulders — though the occasion happened to be a birthday party for a raging drunk Norman Mailer, who put his hands all over her. She dined with Lou Reed at the writer Lisa Robinson’s apartment. She and her b.f. shared a house with the Blue Oyster Cult, back when those metal pioneers were called the Soft White Underbelly. She met the young Iggy and Alice Cooper and Marc Bolan of T-Rex and such monumental rock elders as Muddy Waters and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. She was at the celebrated Rock Writers Convention in Memphis in ’73, where the original lineup of Big Star, Alex Chilton’s band, played their one and only gig, and on the infamous Hells Angels boat ride around Manhattan, the same year, where she got to know Jerry Garcia and Bo Diddley, both of whom performed, and where she witnessed the Angels preparing to throw overboard a smarmy young local-TV reporter named Geraldo Rivera. She was in the room when Epic signed a raggedy-ass outfit from SUNY/New Paltz called the Dictators, who would then make the first-ever punk record. An undergraduate Gary Lucas crashed on her couch, a dozen years before he captained Beefheart’s Magic Band and an over-served Lester Bangs passed out in her armchair, a dozen years before he overdosed.

Her kids think of her as their unassuming mom. Little do they know.

Roni was, and is, an artist. She paints and draws (and today also teaches painting and drawing). But she always had a camera, and knew how to use it, and at some point her writer friends, when they needed pictures, started to ask her along to interviews and concerts and parties. They liked her and knew that, unlike a lot of those ego-tripping shutterbugs, she would be, well, quiet and always get the job done. So she has a lot of unique photos. At the same time, she missed a lot of unique photos. She says that it just seemed kind of rude to whip out your camera while chatting with a new friend, even if that friend turned out to be Jimi Hendrix. But then it was precisely that sense of consideration that made writers invite her along in the first place.

And anyway, who knew these young musicians would soon be dead? Or immortal.

I first met Roni in the Village on West 4th Street. Yes, “Positively 4th Street,” if that’s not too cute for a rock ‘n’ roll love story. If you know us, you can skip this next part because I’ve told it a million times. But it really is a true story, even if it’s also a little cute. I was in Jimmy Day’s bar with a couple of friends when a couple of chicks caught my eye through the picture window. I ran outside and grabbed one by the arm and asked her to come have a cocktail. To which she replied: “Get your hands off me!” Whereupon the two chicks, one with a fresh tattoo halfway up her forearm (back when tattooing was illegal in New York!), continued briskly east on 4th, while I backpedalled in front of them. I tried various forms of begging and pleading and got only silence in return. Finally, I asked: “Where are you girls going?” And the girl I had grabbed took the bait.

“The Bottom Line.”

The Bottom Line was a club, the music industry showplace in NYC in the mid-seventies, the place where Bruce Springsteen would launch Born to Run (we were there) and Elvis Costello would launch My Aim Is True (ditto). Having worked as a latter-day rock critic, I knew most everybody in the music industry. So I’m thinking, bingo.

“Hey,” I offered, “I can get you in free.”

“How can you get us in free?” she asked.

And I proceeded to explain how that night’s performer, a “new Dylan” by the name of Elliott Murphy, was on RCA Records, and I was good friends with the publicist at RCA and blah-blah-blah. And she said flatly:

“We’re already getting in free.”

Incredulous, I asked, “How are you getting in free???”

And the get-your-hands-off-me girl replied: “I’m a photographer, and she” — pointing to the newly tatted Helen Wheels — “is a singer.”

“What’s your name?”

“Roni Hoffman.”

“Roni Hoffman! I sent you a check last week. I’m Robert Duncan, from Creem.”

So the girls came in and had a few cocktails, and one of them stuck around for more decades than we’d ever admit.

But I bring all this up for two reasons. The first is that, after much cajoling from friends like Mike Lemme, I finally convinced Roni to go through these anonymous cardboard boxes I knew were buried deep in a funky shed at our house. I knew because, periodically, a publisher or record company or movie studio would call in search of a rare photo they had heard she might have — for instance, the Almost Famous folks wanted a certain Lester shot and Rhino Records wanted the only performance photo of the original Big Star for that band’s box set — and Roni would disappear for an hour or two to dig around in the shed and through the boxes and, some of the time, would turn up the priceless picture in question. Only some of the time, because being a photographer more focused on painting and drawing, she had never really bothered to fret about which magazine or record company or errant rock critic had returned what set of negatives to her back in the day.

And anyway, who knew these young musicians would soon be dead? Or immortal.

But I convinced her to begin reclaiming her past for the modern era, and for the kids (who are not really kids at all anymore), and to make some digital noise. Have a website, for her art, as well as her photos. And though some of the scans had to be made from contact sheets or ripped prints and some of the other pictures are gone for good (and some never got taken), finally, she does.

So the first reason I bring all this up is to convince you to check out ronihoffman.com.

The second reason is that, ten months after we’d met, more decades ago than we’d ever admit, I married the girl I grabbed on 4th Street. And Sunday’s our anniversary. And I just wanted to say I love her. Still. So, happy anniversary, Hoffman. I’ll be home soon.