News

On this Easter Sunday of Passover weekend, we should all be grateful for the latest resurrection of Terry Adams — he of the perennially passed-over NRBQ, America’s greatest cult band.

His new album’s called Holy Tweet. And while it’s not out till the end of the week, it got a sweet review from Ben Ratliff in today’s Times, and you should definitely plan on appending it to your music collection. And even if you don’t grok it at first, even if it seems too silly or too poppy, too accessible or even too willfully obscure, you’ll eventually discover that you’ve not only had a good time, but learned something. And then you’ll see the genius of Terry, the Hohner Clavinet-slapping heart of the Q.

I’m not the first to tout NRBQ — Elvis Costello left out the “cult” part when he called them “the best band in America” and Penn Jillette said they were the “best band in the world” — but I could’ve been. My life has crisscrossed theirs at odd intervals for 40 years.

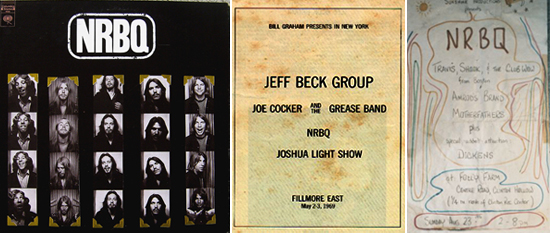

NRBQ (which stands for New Rhythm & Blues Quintet/Quartet) were a Next Big Thing when their first self-titled album came out on Columbia in 1969. On the other hand, I was just another NBT-aspirant, nose to the glass of New York’s 48th Street music row, when I first encountered the band, parading in self-consciously single file down the opposite sidewalk. Even the way they walked seemed unique and, I would soon discover, uniquely Q.

That first album is at least a minor classic and, like the dozens of albums that followed, turned out to be reliably more than first meets the ear. And, as such, secretly influential, too. For instance, if you’re a rock fan who likes Sun Ra, you surely owe it to that record, which included among its improbable mishmash of rock ’n’ roll, rockabilly, country, comedy and jazz Sun Ra’s “Rocket #9.”

There were pretty much zero to none rock fans digging Sun Ra in 1969.

Along with most of the rest of the world, I didn’t buy that first album until later, which is when I also become a fan of Sun Ra, whom I would still later experience in his full Arkestra glory at the Village Gate. In any case, Sun Ra was something I learned directly from NRBQ.

Their second album, typically, whimsically, but no less defiantly, shrugged off any record label efforts at career-building. It wasn’t even attributed to the band. It was called Boppin’ the Blues and attributed to Carl Perkins and NRBQ. It was mostly Carl singin’ and playin’ and them backing him up. But while the late, great Perkins, of “Blue Suede Shoes” and Sun Records fame, resides now in the rock pantheon, he was in those days another has-been greaser swept aside by the hippies and their aspirations — and mostly pretensions — to cap-A Art. But I’ll tell you what: Boppin’ the Blues holds up magnificently.

Talk about weird personal crisscrossing: the producer of the album was Murray Krugman — who I think may have also suggested the pairing with Perkins (totally embraced by Terry and co.) — who would go on to partner with Sandy Pearlman (see previous Noise post) to produce Blue Öyster Cult, the Dictators and Pavlov’s Dog, among other decidedly heavier outfits.

But even if they were abetted by Krugman, a Columbia staff producer, the band in every encounter with the mainstream music biz reinforced its burgeoning reputation as headstrong and other euphemisms for pain in the ass, and the second album was its last for Columbia and the fork in the road leading to cultdom.

And my high school prom.

You had to see them live, and, in 1970, I did, and that was that. The original NRBQ. And the sidelight was that the opening act at the prom — or senior dance, as it was called — was the Wildweeds, featuring Al Anderson, who within a couple of years would take his place as NRBQ’s longest running and definitive lead guitarist and vocalist, before splitting 20 years later to make some money as a Nashville songwriter. Afterwards, checking out the new Perkins/Q album with classmate Tom Beckwith, I couldn’t have been more pleased. It rocked. Or rockabillied. Or something’ed — it was different from all the other new rock music. And besides, anything that swept aside the hippies was, by 1970, alright by me.

A year later I was at the same Village Gate where I was eventually to see Sun Ra (and was eventually to work as an usher for a show called National Lampoon’s Lemmings, featuring such unknowns as John Belushi, Chevy Chase and Christopher Guest), in the middle of a very long night. Can you precisely pinpoint the drunkest you’ve ever been? I can. It’s not something I’m terribly proud of. But maybe it taught me to be a bit more careful around booze?

I was 18 (drinking age in Seventies NYC) and had attended a free cocktail party at my old grade school (hey, I said free) and got so wasted that I wound up, among other shameful things, in a wrestling match with the principal, who was endeavoring to throw me out. Escaped in a cab with some fellow “alumni” and headed toward the Gate, only to get stuck in traffic. At which point, I bolted the taxi and took off running — or so my friends, who chose not to run after me, would report. Most bizarrely, they get to the Village Gate, and I’m already there, the only possible explanation for which is that I leapt from one cab, ran around the traffic clot, and grabbed another.

Before the show, for no reason, I make my way backstage, where someone makes the mistake of letting me in. It’s not five minutes before I’m being tossed, I later gather, as a roadie restrains Frankie Gadler, their great lead singer of the time, from murdering me with his fists. To this day, it remains opaque what I, as a loving and devoted Q fan, might have said or done. (Though it reminds me of the time when one of the guys in Chicago had to be restrained from hitting me when I asked him, upon meeting, “Hey, how’s your life?” Which he misheard as “How’s your wife?” As he was in the midst of a nasty divorce, it evidently wasn’t so good.)

There were two sets that night, and they cleared the house between them. But they apparently missed the guy curled up under the table in one of the back booths. I woke up as a new crowd was filing in (somebody stepped on me?), at which point I espied a few random acquaintances from high school — to their eternal chagrin. The night went on well past daybreak, me yammering at the luckless ex-schoolmates, but the second show kicked ass, and I was to see NRBQ many more times over the years, including on one last occasion at New George’s in San Rafael, CA, of all places, four blocks down from D/C’s old office. And while the group’s unique and happy, multi-genre mishmash — such a clear reflection of the omnivorous Terry Adams — never did change that much, it also never did disappoint, as NRBQ waited for the rest of the world to catch up. Which it never did.

The Q has been on “hiatus” for a couple of years now, though Terry and other band members still play and record, mostly independent of one another. I could go on about this band that also discovered the Shaggs(!) and brought song-poems to our attention, but will stop with a story that surfaced as I was wallowing in their legend on the web, a story that suggests NRBQ not only invented Spinal Tap and punk, but killed off the Sixties.

Disgusted with the hamfisted pretension of much of the era’s rock, the band encouraged their roadies, most of whom had never played an instrument, to start a group. That band was called the Dickens, and they would periodically open for the Q or, on one infamous occasion, close for them. The evening in question, early in 1970, when the bloom was still on the rose about the Q as Next Big Thing, Jimi Hendrix showed up at Ungano’s, a club on Manhattan’s upper west side, to check out Terry and the boys. NRBQ finished its set, and Hendrix was making for the exit when Terry reached out and urged him to stay for another hot new band. Hendrix, who would die months later, returned to his seat. At which point, the Dickens came on to let their freak flag fly, thrashing away enthusiastically, loudly and utterly incompetently.

Donn Adams, Terry’s brother, told Phil Milstein of Spectropop the rest:

We were just blaring out this shit, and then we went into our big finale. We started to roll around on the floor, with the guitar necks rubbing. He had a date with him, and they had checkered tablecloths at Ungano’s, and he took one off and was waving it around, kind of like a white flag of surrender. After a while he got up and started giving peace signs and ran out of the room.

After that he went to Europe, and that was his demise. I always felt like maybe we just crushed him, like he thought we were making fun of him, ’cause we’d been rolling around on the floor rubbing the bass neck and guitar neck together and feeding back. But it was never meant to be that — we weren’t making fun of him.

Holy Tweet, indeed.