News

As if I don’t have enough to do.

Now Sandy Pearlman, the man who coined the phrase heavy metal, produced the Clash’s US debut and was the one guy who could have said “more cowbell” during Blue Öyster Cult’s “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” sessions (he was also their producer), wants me to write him a cheat sheet on the Mars Volta for the music class he teaches at McGill in Montreal. I was elected because I tried to get Sandy to go with us to an MV show at the Greek in Berkeley last year, because I thought that, with his lifelong affinity for the bombastic-fantastic, he should definitely be plugging in to these guys.

But I have not a clue why I like them.

I mean, it would never occur to me to teach a college class with the subtitle “From Bruckner to Heavy Metal.” I don’t even know who Bruckner is, except for what I infer from Sandy’s rants. Sure, I like all kinds of music — rock, metal, Chinese traditional, bebop, old country. But not prog rock.

Once upon a time, at the Fillmore East, I was forced to endure a Hammond B-3 noodlethon by the Nice, Keith Emerson’s original band and progressive rock’s founding fathers, as I awaited some headliner (which, based on a cursory web search, was probably Ten Years After — speaking of noodling). And way back when I was playing music semi-professionally, I promptly quit one longtime band after they decided to cover a Jethro Tull song. (Not strictly prog, Tull was/is surely the moral equivalent.)

Suffice it to say, I hate prog.

And love the Mars Volta.

Which seems as good a place to start as any as I attempt to help Pearlman educate Canucks.

First off, prog sucks because prog thinks it doesn’t suck. In fact, prog thinks it’s the only form of rock that really knows music. As if knowing music, or musicianship, is any criterion whatsoever. Unless it’s a negative criterion.

Prog arose at the end of the sixties as certain sixties musicians started to grow older, started to lose their fire and started to thinking. Started to thinking that a grownup should play more than three or four chords. Started to thinking that jazz or classical players were the real models for aging musical careerists. Started to thinking that seriousness and quality and longevity were all about chops — and all about thinking.

In short, prog arose as a group of rockers started looking for r-e-s-p-e-c-t. Instead of looking to systematically heap dis-r-e-s-p-e-c-t on the stultified forms and standards that rock had long since stomped.

So, it’s easy to see how prog rock sucks.But it’s harder to see how a group that entitles its ten-plus-minute songs “Cassandra Geminni [sic]: E. Sarcophagi” or “Miranda That Ghost Just Isn’t Holy Anymore: A. Vade Mecum” doesn’t. (Note: A colon in a song title, especially when followed by a letter of the alphabet indicating, a la classical music, that the song is actually a movement in a longer cycle, is pretty much incontrovertible evidence of prog-ness.)

It’s harder to see how a group that channels Rush, Yes, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Queen and post-Something/Anything? Todd Rundgren could ever make the cut to cool.

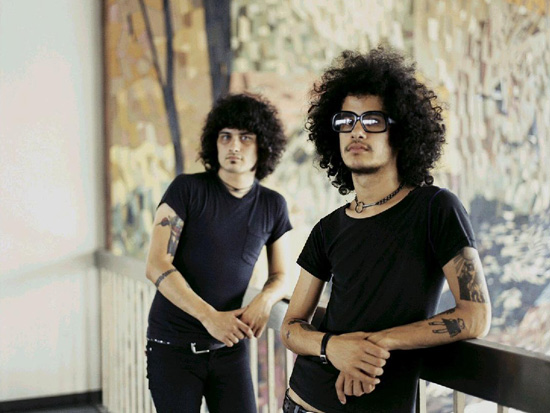

For sure, all the sins of prog are present in the Mars Volta, from the excessively poetic song titles and sci-fi-ish nonsense lyrics to the formal, pseudo-classical ambition of the album structures to the supersonic technical chops of guitarist Omar Rodriguez-Lopez, who co-founded the group (out of the ashes of At The Drive-In) with singer Cedric Bixler-Zavala to the very name of the band. The Mars Volta.

Hah.

But make the cut it does. This improbable entry from the irredeemable prog realm turns out to be nothing less than irresistible — pre-intellectually, trans-technically, ultra-viscerally irresistible — one of the most electrifying bands of the day. Which is to say the Mars Volta is pure rock.

And you don’t have to attend one of their live shows to know it. But if you do, you will know it (even, alas, at the Greek, where Berkeley-hippie noise ordinances keep eleven-enabled amps to distinctly un-visceral single-digits). Tiny Omar, who it’s easy to imagine as the nerdish A+ guitar student, the dedicated learner of scales and modes and harmonies and pick techniques, spins across the stage like a dangerously skittering top, a whirling devish mad with the music, Carlos Santana (there is a physical resemblance) on crank. (And, considering that Omar used to be a degenerate tweaker, the comparison is only apt.) Meanwhile, from the center of Cedric’s big ball of ‘fro, comes a keening wail that penetrates the band’s big ball of sound to scrape bloody fingernails across a black sky. Even in volume-deprived Berkeley.

But you don’t have to attend one of their live shows (though you should, you really should). The records have it all. Because mixed in with the Rush and Yes and ELP is Henrdrix and Led Zeppelin and, yes, Carlos Santana. And, yes, there’s jazz, too. Not the polished, technical kind that might make its practitioner all the more credible as a “real” musician and true “virtuoso,” but the impolite, still-nigh-unlistenable kind, of Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler. There’s some Dead — not the American Beauty pastorale, but the druggy, twisted experimental worlds of Axomoxoa. There’s even Blue Öyster Cult — “Son et Lumiere” could be an extension of the feedback breakdown in “Reaper.” And then, when it really gets weird (for prog, if not for rock in general)(though not, perhaps, for rock en espanol), there’s Tito Puente and Eddie Palmieri and Cachao. Classic mambo and salsa percussion mercilessly driving hot rock tempos to a transcendent frenzy.

It’s all that. And none of that. Because certainly Latin and jazz and experimental have all been melded to rock before. And some has even been melded to prog. After all, genre stew was one of prog’s first moves — a little Bach, a little Beethoven, a little Coltrane.

No, while the Mars Volta may have managed to make a fresh version of genre-meld, the real difference, the real reason I was so completely seduced, against all better judgment and lifelong prejudice, is this.

The essence of progressive rock is control. The essence of the Mars Volta is chaos. Things going out of control. Surrendering to the happy accident — the busted speaker cone, the feeding-back microphone, the short-circuited guitar cable or noisy knob. Where prog rock would seek to build its own beauty, the Mars Volta — like every other great rock band before it — finds the beauty in life’s inexorable tearing down.