News

It is dark and it is cold in January in Detroit. Darker and colder than you’re imagining now. And you are broke. You’ve been amicably tossed, but tossed nonetheless, from your railroad flat in NYC because your childhood buddy, Mark the Shark (he of later Studio 54 celebrity), who more or less owns the place, wants his girlfriend to move in. Actually, she’s in already — they just want a little privacy. Besides, you are a few months behind on the rent, as dirt cheap as it might be, because you are really broke.

And here you are. Detroit in the dead of January.

You know John Morthland from Sausalito, where you lived for ten months, on a lark, after abandoning New York the first time and whom you had met through Ed Ward, the ex-Rolling Stone writer (now “rock historian” on Fresh Air), who gave you your start with an assignment to review Thomas McGuane’s 92 in the Shade. John Morthland’s a really good writer and editor and an amazingly prescient musicologist who was first to discover a lot of things pop-cultural that eluded most rock critics, or at least white ones. Things like rap music (before it was hip hop), Sacred Steel and Moe Bandy. He’s in Detroit to be interim editor — interim, because John is strictly freelance or die. And you know him, it should be clarified, only pretty well, though that may be as well as most anyone knows silent, staring, inscrutably smirking John.

You don’t know Lester.

You know of him, but barely, and as much on the strength of that seemingly concocted name — Lester Bangs — as his writing.

And Creem is a magazine you only ever see on the newsstand in the Astor Place subway station, en route to and fro NYU. It’s that rag out of Detroit, with all the same peculiar passions on display as in that Detroit rock festival they broadcast on Labor Day on one of those cheesy local NY channels, WNEW-5 or, worse, WOR-11. The Stooges, with that Jagger-wannabe who calls himself Iggy, throwing his bleached-blond, shirtless self into the crowd, walking on people’s hands. Or Alice Cooper, thinking it’s some kind of profound statement about pop fascism to try and hypnotize a crowd with a pocketwatch. The “revolutionary” MC5. Or even Grand Funk Railroad. Passions like that. Plus, the magazine looks like Hit Parader or one of those teen ’zines so beneath you at this point, when you’re all of 21. So you’ve barely even read Creem when you start freelancing for it (thanks to Morthland and Ward) and then working there.

The name is concocted, of course, just not the part you think. His Jehovah’s Witness mom, you discover when comparing driver’s license photos, named her baby boy Leslie. For obvious high-school-torment reasons and perhaps as tribute to the jazz saxophonist (last name Young, nickname Prez), he converts that to Lester. And could there be a better brand for a rock critic, if not the greatest ever rock critic, if not, more importantly, one of the few to transcend that dubious pigeonhole?

Lester Bangs. And certainly, at 24, he’s well on his way to living up to it.

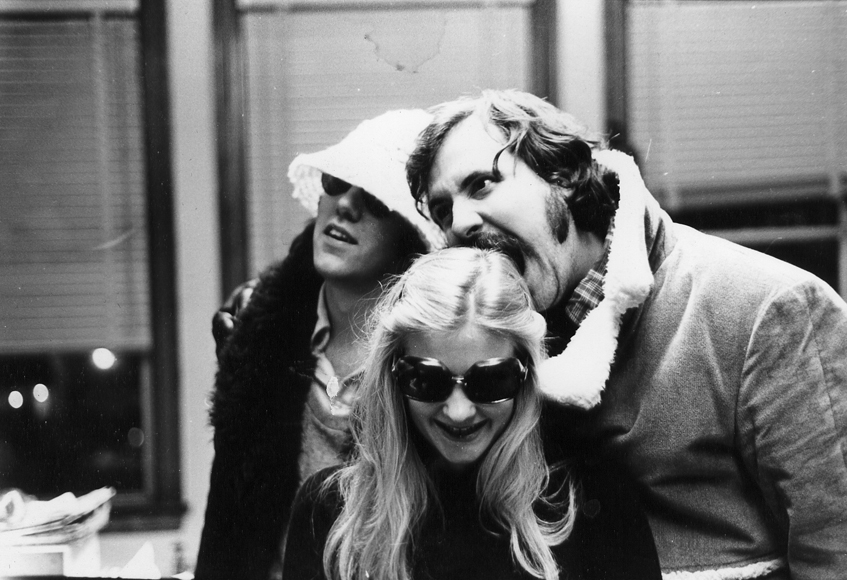

Lester and Morthland, two relative strangers, are helping you with your motley collection of bags, in the middle of winter and night in the dingy Detroit airport. Morthland, his same old inscrutable self, accompanied by the gee-whiz-goofy, glad-to-meet-ya, all-American, mustachioed, budding-beer-bellied, loudmouth kid. “Hey, I’m Lester Bangs!” he says, thrusting his hand, as if you know. But who could be nicer?

Driving away from DET in Lester’s rattletrap, red muscle car (Camaro, pretty sure), you pass the giant Uniroyal tire that’s a landmark hereabouts. Eight stories high, and nearby a light-up display ticks off the number of tires produced to date (at least, that’s how you picture it now). The Motor City, it wasn’t going to be like this. Not sure what you pictured that last night alone in the NYC apartment with Shark and Kate one cubicle over, but not this. But, of course, it is exactly this. What else could it be? A land apart, geographically, economically, culturally, with round-the-clock assembly lines, Iggy Stooge and Lester Bangs.

You can’t know at this moment, bouncing around in the cluttered back seat trying to keep up conversation over the Camaro’s throaty roar, how the Detroit Wheel is turning for you.

The first night you meet Lester Bangs is the first night you meet Wanda. Wanda’s the one who, uncomplainingly, night after night, delivers “bolos” of beer to your booth in Pasquale’s on Woodward Ave. In the year-and-a-half you’re in Detroit — well, Birmingham, a few miles out in the ’burbs — you never get clear on whether bolo is a recognized regionalism or just a Pasquale-ism, but what it signifies is a big, heavy, stemmed-bowl of a glass that carries damn near a quart of alcoholic liquid.

Wanda never cuts you off — not even when the bolos induce pathetically flirtatious behavior in her direction. Wanda even seems to like you. Even laughs at your jokes.

You meet Wanda because, rather than driving all the way home to the communal house where many of the Creem staff lives, Lester and John take you to Pasquale’s. Thankfully. Because there’s nothing like a battery of bolos to take the edge off feeling displaced on your first night in the dead of Detroit winter.

(Twenty-five years later, you return to Woodward Ave., and Pasquale’s, on a cross-country trip with your son. And who greets you at the door but you guessed it. Incredibly, she hasn’t changed much. More incredibly, she’s kind enough to say she kind of remembers.)

Pasquale’s quickly becomes part of the pattern. The pattern being, go to work at Creem, then get drunk at Pasquale’s. Sometimes in between those, or instead of one, you meet rock stars. A couple of times, Lester decides he has to get healthy and lose weight and switches from Pasquale’s beer to its house wine, proceeding to drink the same, or greater, quantity of liquid, but somehow feeling better that it arrives in a carafe — or four or five — instead of a fattening bolo.

Lester is a drunken clown. And you’d never fire a glance at the loud, obnoxious booth in Pasquale’s, as many an angry patron does on many a night, and know that he’s any different from the drunken clowns he’s with. John or me or, later, Air-Wreck.

But he is.

Lester’s mad. And his madness is inextricably linked to his genius. Which may be a cliche, but is still true. While the other drunken clowns may be more or less talented, Lester’s in his own league. Drunk, sober, on a handful of Valium, a snootful of Robitussin or a couple tabs of Dexedrine, you watch as Lester unspools from that big head with the subcutaneous bump reams of writing that is always one part impenetrable jabber and one part brilliant insight and imagery. One day he hands you a manuscript that some magazine (maybe even Creem) has previously refused. Titled “John Denver is God,” it runs an unconscionable 80 pages. Turns out, with a few judicious edits of the parts where Lester’s intoxicants got the upper hand, it’s 40 pages of gold. And now a classic.

Want to be discouraged as a young writer? Share an office with that for a year-and-a-half. While you struggle to squeeze out a few sheets of decentness, Lester — head back, eyes shut, Art Tatum of the typewriter — blurts out literature by the ton, listening to Metal Machine Music.

Speaking of which, don’t let anyone ever convince you to buy it, download it or, heaven forfend, put it in your ears. Don’t let anyone ever convince you it’s anything but unlistenable and a spiteful trick on RCA Records by Lou Reed in his speed phase. Better to listen to the hydroponic hippie farmers who live next door to you in Fairfax and run their power-saws all day. Because Metal Machine Music, objectively speaking, is worse.

Lester loves it. Truly. You’ll wonder later if his loving Metal Machine Music doesn’t also link inextricably to his madness. But, in the meantime, through his exertions, this insane record becomes part of the rock canon. And Lou Reed, Lester’s hero and faux nemesis, becomes part of the rock pantheon.

You want to say Lester has as good a pair of ears as Morthland, but the truth is he has a better megaphone — louder even than the difficult, obscure and/or incompetent artists he touts, like the MC5, the Stooges, the Dictators, Kraftwerk, to whom hipsters across generations and geography would soon learn to genuflect.

But make no mistake that’s about Lester, not you.

The Detroit Wheel turns again when you depart Creem for New York in a huff after your boss and publisher Barry Kramer wants to not pay you for not showing up (the gall!), and you find not one, but two, crazy-cheap apartments and call Lester, who’s constantly threatening to go to New York anyway, to join in. But this time he does it.

It’s the warm spring, as pretty a day as 9/11 and faraway from Detroit winters, when he rolls up with girlfriend Nancy. And while the context suddenly seems strange to you — after all, Lester = Detroit — so does Lester, who’s as sunny as the day. Lester’s sunny about setting up housekeeping, sunny about CBGB’s, and sunny about finally moving up to what he perceives as the big leagues. Where, he perceives, damnit, he belongs. So those two funky apartments on top of that funky, fifth-floor, cockroach walkup at 542 Sixth Ave., above Gum Joy old-school Chinese restaurant, become, for a time, another Creem commune.

Lester, Nancy, you and your girlfriend, Roni Hoffman, the artist and photographer.

Roni knows Lester before you, through her old rock writer boyfriend. Roni, whom you meet just months ago for the first time on Fourth Street in the Village — Positively 4th Street — when you, in your cups, grab her and tell her you can get her into that club the Bottom Line for free. But she’s already getting in for free — she’s a photographer. What’s your name? you ask. And when she says it, you say: Hey, I sent you a check last week from Creem. And so she comes in the bar. And so another turn of the Wheel.

And all of us happy together in “Gum Joy Towers.”

When Lester needs pictures, he gets Roni to shoot them (see above). When Roni needs a cup of sugar, she goes next door to Nancy. And when you want to go drinking one night early in the New York days, you knock on Lester’s door, only to find out that he and the g.f. are going to take it easy tonight.

That’s how sunny: sometimes he’s even sober.

But it turns again when Nancy departs. The madness rises. And soon Lester completely transforms into “Lester Bangs,” performing himself with abandon — while at the same time having no choice in the matter — and disappearing into Austin.

Jook Savages on the Brazos was the name of the album he finally went and made in faraway Texas, performing himself with abandon.

That first dark, winter night in Detroit, Lester is warm. Over the next month or so, he turns cold. It’s high school, for sure. Though you’re not sure why. Not sure, at first, it’s even happening. Ultimately flattered to think he views you as a threat (though not as a writer).

But it isn’t fun, and it’s a part of Lester you see again, later. A part that would, as much as the stupid fight over the beer that Legs McNeil expropriated from your fridge, cause the final split — later, after you’d become so close.

Later, after you’d become so close, you’re rescued by Lester and Nancy when you stagger into the Bells of Hell like you’ve been shot. Broken ribs (or so it seems) after a fistfight with Mark the Shark, who’s in training for Golden Gloves. Roni’s gone then, temporarily, to California, and they take you in and put you in their bed (so they explain). And you wake up in the morning with — wait — Nancy on one side and — wait — Lester on the other. Superfreaks? Nah, after Lester gave you the Valium, they couldn’t wake you up to send you even the 30 paces home.

Later, the other time you, well, sleep with Lester, Air-Wreck can’t wake either of you in the back of his van, after a night of Quaaludes (thanks, Mr. Hollywood) and booze, and so — not really meaning anything, just pretty damn fed up — he leaves you parked outside his parents in another dark Detroit winter to freeze. And without the other, piled together like a couple of corpses, you probably would have.

Later.

Later, you go with Lester to help him buy a suit for a wedding, at which of course he gets ripping drunk and high. Next morning you find, sitting before the humming Selectric with his new suit on — matching conservative vest, pants and jacket now soaked through with sweat — Lester Bangs banging away. Doesn’t acknowledge you, doesn’t barely look up for hours. Not sure what piece of genius emerges from that mad session. Sure something did, though.

Later, he gets you pissed over a girl. An ex-girl. Just being that other cold, careless part of Lester that doesn’t come up in discussion in his hagiographic posthumy because, what’s the point? And you know what, you agree. Nobody’s perfect, and Lester’s special.

Later, Roberto, the landlord, who’s your age and lives on the second floor with his sister and immigrant mother and seems to look on this whole drunken, rock ’n’ roll scene with both amusement and horror, knocks on your door and says, Robert, I think there’s something wrong with Lester, and you go next door into that otherworldishly stinky room where you’d last been, after the split, to tell him Barry Kramer had died, and he’s lying on the couch looking straight up at you and you say loudly, Lester, Lester, Lester, and pick up his wrist and hold it in the air, but you don’t know how to take a pulse anyway and anyway you can see, you can clearly see, even if you can not believe it — how can you??? you just heard him stumbling up the stairs, classic Lester-style, a few minutes ago. Minutes, really.

But.

“But I can guarantee you one thing,” Lester Bangs wrote a few years earlier in his Village Voice obit for the King, “we will never agree on anything as we agreed on Elvis. So I won’t bother saying goodbye to his corpse. I will say goodbye to you.”

But back in those first months of that first Detroit winter, darker and colder than you’re imagining now, you know the whole thing is turned around when you hear Lester on the phone telling his friend, the publicist from Capricorn Records (you remember it perfectly, at a time when you’re all too likely to forget), he’s “finally met someone as funny as me. His name’s Duncan.”

So maybe that’s it, why you become so close. Because for a while, he keeps you out, and, later, Lester — who could be pretty damn funny and even pretty damn generous — lets you in.

And, considering his genius (quite apart from his madness), something like that is something to remember, almost 30 years since he’s gone.

But, of course, a guy like Leslie Conway Bangs, he’s never gone. When that Detroit Wheel turns, it never turns back. And so just a few months ago, via Facebook, of all quintessentially not-30-years-ago things, comes a message from a writer named Rob O’Connor asking if you’re the same one from Detroit and Creem and Lester.

And in the end, inescapably, you are.